Home

Land Rover Discovery in Africa

| I prepared the following Article for an International Land Rover Magazine in the mid 1990's. We had been using two Land Rover Discoveries in an extreme environment and they wanted a popular opinion on how they performed. |

“They tell us this is a table land. If it is, they have turned the table upside down and we are scrambling up and down the legs.” – A comment on Ethiopian scenery made by a British soldier during the Napier Expedition of 1867-68.

Working overseas for many years in developing countries has made me immune to “Culture Shock”; or so I thought. My friend from the Canadian mid west was a certain candidate for culture shock. This was, after all, his first excursion outside Canada. As we headed out of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, in one of my two Tdi Land Rover Discoveries, I was intrigued to find out what a prairie farmer would make of Ethiopian traffic. Would he make a comment about the convoys of donkeys or herds of goats crossing the road, or maybe he would ask why the cows graze on the dual carriageway central reserve in the city? Yet again he might ask why do Ethiopian woman carry enormous loads of fire wood into the city on their backs? (well; the men wouldn’t do it, would they?). He might be intrigued about the appalling condition of some of the vehicles on the road? No; none of these.

Working overseas for many years in developing countries has made me immune to “Culture Shock”; or so I thought. My friend from the Canadian mid west was a certain candidate for culture shock. This was, after all, his first excursion outside Canada. As we headed out of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, in one of my two Tdi Land Rover Discoveries, I was intrigued to find out what a prairie farmer would make of Ethiopian traffic. Would he make a comment about the convoys of donkeys or herds of goats crossing the road, or maybe he would ask why the cows graze on the dual carriageway central reserve in the city? Yet again he might ask why do Ethiopian woman carry enormous loads of fire wood into the city on their backs? (well; the men wouldn’t do it, would they?). He might be intrigued about the appalling condition of some of the vehicles on the road? No; none of these.

The difference between the American and the European continent is much wider than I thought. His question shocked my “Culture” to the core. Used to driving large automatic American cars he just couldn’t understand why anyone would contemplate buying a vehicle with …….”a gear sick?”. “Gee did you buy this Land Rover with a manual shift for a reason”?

I am a Civil Engineer, responsible for the supervision of the construction of a new road in Ethiopia. The road is 700 km (420 miles) long and passes through some of the most remote and rugged terrain found in Ethiopia. It is a basic standard road having a surface of gravel but when completed it will be passable all year round. There are few roads in this remote area making access extremely difficult.

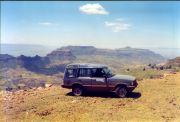

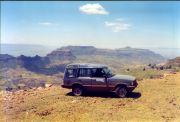

The scenery is superb. There are large plateaux which are incised by immense deep valleys gouged by tributaries of the Blue Nile River and then sculptured by wind erosion. The valleys are over a kilometre (nearly one mile) deep and are reminiscent of the Grand Canyon.

The scenery is superb. There are large plateaux which are incised by immense deep valleys gouged by tributaries of the Blue Nile River and then sculptured by wind erosion. The valleys are over a kilometre (nearly one mile) deep and are reminiscent of the Grand Canyon.

Vegetation is sparse. Most of the large trees have been felled or burned leaving a soil highly susceptible to erosion. Women, Mules or donkeys are the traditional forms of transport although the vast majority of people walk. If you speak with an Ethiopian farmer about transport, you are either talking about his donkey or his wife.

Time has stood still in Ethiopia and after 30 years of war and famine, time is now ripe for progress.

The problem with building new roads is that there are, obviously, no or few existing roads. Richer countries would turn to helicopters to reach these inaccessible places; the budget allowed only for four wheel drive vehicles. We purchased two Tdi Discoveries which have a tropical specification. No accessories have been added.

They have completed approximately 55,000 kilometres each within a period of eighteen months almost exclusively off road. I admit that on rare occasions they have been spotted, parked on the tarmac outside a favourite night spot in Addis!

Nevertheless these vehicles are being tested to the limit. The few roads that are available are extremely rough and there are no service points along the route of the road. Even a puncture repair is not possible for the major length of the new road route. Dust and vibration create severe wear and tear on the body, transmission, suspension and steering parts.

We carry sufficient tools and equipment to carry out minor repairs. Shovels, pick axes, tow ropes are standard equipment. The two vehicles travel in pairs on the more difficult trips. However, pressure of work does not always allow this luxury and frequently the vehicles travel into remote territory singly.

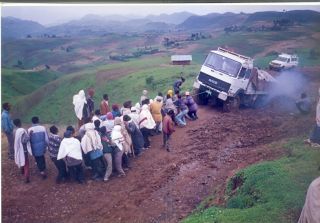

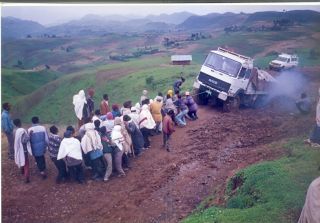

Tackling severe or technically difficult sections when one is alone in a remote location is risky. Usually, however, there are plenty of willing hands when the going gets too tough. The usual fee for local people helping out is one Birr (10p). It is difficult to break the bank, even on my limited budget, at that rate. There was one time when I employed 30 people to assist passage over a washed out river, and that only cost my £3.

The worst problems associated with driving these roads are experienced during the wet season which occurs between July and September. Even an innocent looking pot hole can turn into something extremely nasty. Some are deeper than you think. Trucks, delivering food aid, often become bogged for several days. The fun is to find the way round these obstacles.

On the plateaux, the surface material is black cotton soil. When it is dry it is extremely hard and can be traversed with little difficulty. When it is wet, vehicles sink to the axles. If you encounter this material on steep slopes then beware because you are going to have an interesting time. On more than one occasion I have found myself loosing traction on a steep and narrow pilot track with a 1,000 foot drop to one side.

Why build new roads through this terrain? Well the area is populated by extremely poor people who live on the edge of starvation. The area has been frequently affected by famine; remember Band Aid relief effort of 1985. Soil degradation is extensive and farmers till ground which is extremely poor. Crop yield is extremely low and subject to frequent failure. Supply of food aid is therefore, unfortunately, always necessary. Health centres are few and far between. Sick people are usually carried in their beds for many miles along trails which have vertical distances of over one kilometre. The new road provides a life line to the people living in these areas.

Why build new roads through this terrain? Well the area is populated by extremely poor people who live on the edge of starvation. The area has been frequently affected by famine; remember Band Aid relief effort of 1985. Soil degradation is extensive and farmers till ground which is extremely poor. Crop yield is extremely low and subject to frequent failure. Supply of food aid is therefore, unfortunately, always necessary. Health centres are few and far between. Sick people are usually carried in their beds for many miles along trails which have vertical distances of over one kilometre. The new road provides a life line to the people living in these areas.

The new road, when complete, will connect the towns of Alem Ketema, which is about four hours drive north of Addis Ababa, to the town of Sekota in the north of Ethiopia. The straight line distance between these two centres is only 165 miles, yet the road will be over 420 miles long. The exact distance will not be known until survey work is completed sometime in the near future, however, the road will cross six major valleys. It is a gravel surface road and we have already built 170 miles on four separate fronts. Several bridges have also been constructed. This already provides access to several villages normally cut off from the outside world during the wet season.

The new road, when complete, will connect the towns of Alem Ketema, which is about four hours drive north of Addis Ababa, to the town of Sekota in the north of Ethiopia. The straight line distance between these two centres is only 165 miles, yet the road will be over 420 miles long. The exact distance will not be known until survey work is completed sometime in the near future, however, the road will cross six major valleys. It is a gravel surface road and we have already built 170 miles on four separate fronts. Several bridges have also been constructed. This already provides access to several villages normally cut off from the outside world during the wet season.

One of the local people’s main problem during the wet season is crossing rivers. Ethiopian rivers rise rapidly and stay high for several hours before dropping to a trickle. People sit at the side of the rivers for long hours waiting for the flood waters to recede. Many impatient travellers try to cross early and are washed away. We understand that at one river, now spanned by a new bridge, the death rate by drowning was eight people per year.

One of the local people’s main problem during the wet season is crossing rivers. Ethiopian rivers rise rapidly and stay high for several hours before dropping to a trickle. People sit at the side of the rivers for long hours waiting for the flood waters to recede. Many impatient travellers try to cross early and are washed away. We understand that at one river, now spanned by a new bridge, the death rate by drowning was eight people per year.

These rivers are often used by the Discoveries to gain access into the interior. Time and again I have proved that access into the most difficult areas can be affected by following these rivers. In the dry season there is not much water. The main problem is the size of the boulders which litter the river bed.

During the wet season these same rivers have to be crossed. The depth of water is not always the main problem, although I sometimes wish we had a snorkel. These same large boulders are rolled down the river and deposited at the fording points. This is a major hazard to the unprotected steering damper.

Rivers rise very quickly, therefore, care must be exercised before crossing. The best was to check is to “volunteer” your boy to cross on foot. If the water is below the bottom of his shorts, then maybe it’s OK. If he is swept away, then try later!

Rivers rise very quickly, therefore, care must be exercised before crossing. The best was to check is to “volunteer” your boy to cross on foot. If the water is below the bottom of his shorts, then maybe it’s OK. If he is swept away, then try later!

Historical places which were inaccessible before the end of the Ethiopian civil war (i.e. 1991) are being opened by the new road. In 1867, General Napier mounted, what was probably the most successful campaign in British Empire history. Using elephants from India and the only local means of transport know at the time in Ethiopia, i.e. donkeys, General Napier mounted an expedition into the remote heart of Ethiopia to rescue British hostages held by the Ethiopian King Theodore. The hostages were held at the natural fortress called Magdela. It is a huge natural rock bastille and was protected by a huge mortar gun called “Sebastopol”. This gun can still be seen at the base of the fortress.

One bulldozer has been dispatched to create a four wheel drive access road to the base of the fortress. It is now possible, for the first time in history, to take a four wheel drive vehicle to the base of this historic site. There is no doubt that this could become a favoured tourist destination in the future.

One bulldozer has been dispatched to create a four wheel drive access road to the base of the fortress. It is now possible, for the first time in history, to take a four wheel drive vehicle to the base of this historic site. There is no doubt that this could become a favoured tourist destination in the future.

The road also passes through the town of Lalibela which is famous for its unique rock hewn churches. There are eleven separate churches which are sculptured out of solid rock during the twelve and thirteenth centuries. The local stone is soft enough to carve yet hard enough to survive the ravages of weather and time. They are quite large and are used extensively by the Ethiopians who consider them to be the greatest wonder of the world.

Access to Lalibela is extremely difficult by road in the wet season, that is of course until the new road is completed. This should be achieved before July 1996.

Access to Lalibela is extremely difficult by road in the wet season, that is of course until the new road is completed. This should be achieved before July 1996.

From Lalibela, the new road will continue a further 200 kilometres north to the town of Sekota where it will link to another road leading to Axum, purportedly the birth place of the Queen of Sheba.

Navigation is essential in this type of country. What did they do before this incredible invention? It certainly provides confidence for navigating the long and wide plateaux where there are no roads. I have a hand held Magellan GPS (Global Positioning System) which is used for navigation and survey work. It therefore needs to be portable but also needs to operate within the Discovery. I have wired the GPS into the vehicle electrical circuit and it is fixed to the dash by use of sticky backed Velcro. It never breaks free even on the roughest routes. When we have to resort to more basic transport (i.e. mule) I can remove the GPS from the vehicle and carry it. Using satellite navigation on the back of a mule is the ultimate in appropriate use of modern and ancient technology.

Navigation is essential in this type of country. What did they do before this incredible invention? It certainly provides confidence for navigating the long and wide plateaux where there are no roads. I have a hand held Magellan GPS (Global Positioning System) which is used for navigation and survey work. It therefore needs to be portable but also needs to operate within the Discovery. I have wired the GPS into the vehicle electrical circuit and it is fixed to the dash by use of sticky backed Velcro. It never breaks free even on the roughest routes. When we have to resort to more basic transport (i.e. mule) I can remove the GPS from the vehicle and carry it. Using satellite navigation on the back of a mule is the ultimate in appropriate use of modern and ancient technology.

Problems with Discovery? Well there are plenty, but one has to consider the punishment meted out to these vehicles. The key to keeping the vehicle running in this tough environment is regular maintenance and daily inspections. Preventative maintenance is extremely important to ensure things don’t start dropping off. Looking for oil leaks, loose nuts, fan belts etc. every night is well worth the trouble.

Shock absorbers are changed at regular intervals and we have had to renew several steering dampers. A guard would solve this problem but on a limited budget and restraints on foreign currency spending, this has not been provided. We have removed the wheels from the back door to save the hinges and to stop the inevitable dust leakage. Anyone using a Discovery in similar harsh conditions will need to remove the spare wheel from the rear door. Dust and vibration are the two main enemies.

Shock absorbers are changed at regular intervals and we have had to renew several steering dampers. A guard would solve this problem but on a limited budget and restraints on foreign currency spending, this has not been provided. We have removed the wheels from the back door to save the hinges and to stop the inevitable dust leakage. Anyone using a Discovery in similar harsh conditions will need to remove the spare wheel from the rear door. Dust and vibration are the two main enemies.

The central locking system on both cars “bit the dust”. This is no problem because the cars are now manual locking. What is more worrying are the electric windows. If these succumb to the dust and vibration it will lead to an uncomfortable situation. Tropical specification vehicles should be provided with manual window winders set into the door so that you don’t bang your legs. However, to date they have not given any problems.

All equipment is stored inside the car for security reasons. More tie down points are needed to secure tool boxes, jerry cans and the like.

Why do Solihull insist on placing the horn on the indicator stick? Cows, camels, donkeys, children etc. must be made aware of your presence. Travelling fast on a bumpy Ethiopian road entails continuous attention to the horn. The indicator flashes left and right as you press the horn and bounce up and down. Far better to place the horn in the centre of the steering wheel. Maybe I’m just old fashioned. That’s one thing my children would agree with.

Why do Solihull insist on placing the horn on the indicator stick? Cows, camels, donkeys, children etc. must be made aware of your presence. Travelling fast on a bumpy Ethiopian road entails continuous attention to the horn. The indicator flashes left and right as you press the horn and bounce up and down. Far better to place the horn in the centre of the steering wheel. Maybe I’m just old fashioned. That’s one thing my children would agree with.

Driving in Ethiopia is hard. Hard on the vehicle and hard on the driver. Weaving round pot holes, dodging camels, swerving past donkeys, missing goats; you need one hand on the steering wheel, one hand on the horn and one hand on the gear stick Hummmmm – maybe that Canadian had a point!

© Copyright 2010 Brian Barr Consulting Services Ltd.

Home

Working overseas for many years in developing countries has made me immune to “Culture Shock”; or so I thought. My friend from the Canadian mid west was a certain candidate for culture shock. This was, after all, his first excursion outside Canada. As we headed out of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, in one of my two Tdi Land Rover Discoveries, I was intrigued to find out what a prairie farmer would make of Ethiopian traffic. Would he make a comment about the convoys of donkeys or herds of goats crossing the road, or maybe he would ask why the cows graze on the dual carriageway central reserve in the city? Yet again he might ask why do Ethiopian woman carry enormous loads of fire wood into the city on their backs? (well; the men wouldn’t do it, would they?). He might be intrigued about the appalling condition of some of the vehicles on the road? No; none of these.

Working overseas for many years in developing countries has made me immune to “Culture Shock”; or so I thought. My friend from the Canadian mid west was a certain candidate for culture shock. This was, after all, his first excursion outside Canada. As we headed out of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, in one of my two Tdi Land Rover Discoveries, I was intrigued to find out what a prairie farmer would make of Ethiopian traffic. Would he make a comment about the convoys of donkeys or herds of goats crossing the road, or maybe he would ask why the cows graze on the dual carriageway central reserve in the city? Yet again he might ask why do Ethiopian woman carry enormous loads of fire wood into the city on their backs? (well; the men wouldn’t do it, would they?). He might be intrigued about the appalling condition of some of the vehicles on the road? No; none of these.